Dragos Professional Services and the Dragos Platform regularly detect and respond to ransomware outbreaks within industrial environments. Impact and operational assessments of ransomware in this report derive from responding and protecting these environments daily.

Dragos published a previous version of this report for threat intelligence customers on 14 January 2020. Due to the public interest in this ransomware, we are releasing the full report to the public.

NOTE: Since publication, Dragos was informed by an independent researcher that EKANS actually contains a far larger list of processes to kill than initially understood.[a] Further examination shows the process list overlaps with the MegaCortex list cited earlier in this post, indicating significant continuity between these samples, with EKANS only adding obfuscation and encoding to make the process list non-obvious to researchers.[b] Based on this information, EKANS remains an interesting threat to ICS-specific processes but appears to be a continuation of a trend dating back to at least the summer of 2019.

[b] Script and the decoded strings from the EKANS/Snake ransomware – GitHubGist

Executive Summary

EKANS ransomware emerged in mid-December 2019, and Dragos published a private report to Dragos WorldView Threat Intelligence customers early January 2020. While relatively straightforward as a ransomware sample in terms of encrypting files and displaying a ransom note, EKANS featured additional functionality to forcibly stop a number of processes, including multiple items related to ICS operations. While all indications at present show a relatively primitive attack mechanism on control system networks, the specificity of processes listed in a static “kill list” shows a level of intentionality previously absent from ransomware targeting the industrial space. ICS asset owners and operators are therefore strongly encouraged to review their attack surface and determine mechanisms to deliver and distribute disruptive malware, such as ransomware, with ICS-specific characteristics.

Upon discovery and investigation, Dragos identified a relationship between EKANS and ransomware called MEGACORTEX, which also contained some ICS-specific characteristics. The identification of industrial process targeting within the ransomware described in this report is unique and represents the first known ICS-specific ransomware variants.

EKANS underscores the importance for asset owners and operators to achieve visibility into their assets. By taking stock of available assets and connections within an environment, asset owners can understand the potential consequences of an adversary deploying ICS-specific ransomware against a certain asset, the impact to operations or related processes, and take measures to defend against them.

EKANS Background and Discovery

Dragos initially learned of a new ransomware variant, called “Snake” or “EKANS”, on 06 January 2020. [1] After alerting impacted parties and reporting to Dragos WorldView customers on 14 January 2020, the malware received additional media coverage on 28 January 2020. [2]

Analyst Note: Although referred to as both Snake and EKANS in public reporting (“EKANS” being “Snake” spelled backwards), Dragos will refer to this malware as EKANS due to the existence of other malware previously discovered and labeled as “Snake” and attributed to the Turla threat actor. [3] Any further or future reference to “Snake” by Dragos will refer to Turla-associated activity, while the ransomware variant under discussion will be referenced as EKANS.

While investigating EKANS, Dragos observed a list of processes associated with industrial control system operations (ICS). The malware was designed to terminate the named processes on victim machines. This is notable for EKANS because while ransomware has previously victimized ICS environments, prior events all feature IT-focused ransomware that spreads into control system environments by way of enterprise mechanisms. [4] Otherwise, ICS-specific ransomware has mostly included either academic proof of concepts or marketing stunts representing the corpus of activity. [5]

Given the unique (if limited) nature of EKANS for ICS operations, Dragos provides the following analysis.

With a limited set of ICS-specific malware in existence, EKANS, though primitive, represents an evolution in adversaries targeting control system environments.

As a result, even though much recent public reporting on the subject has been hyperbolic in nature, the following covers publicly available information on the first known ICS-specific ransomware examples.

EKANS Ransomware Analysis

EKANS is an obfuscated ransomware variant written in the Go programming language, first observed in commercial malware repositories in late December 2019. The only known, relevant sample has the following characteristics:

File Name: update.exe

MD5: 3d1cc4ef33bad0e39c757fce317ef82a

SHA1: f34e4b7080aa2ee5cfee2dac38ec0c306203b4ac

SHA256: e5262db186c97bbe533f0a674b08ecdafa3798ea7bc17c705df526419c168b60

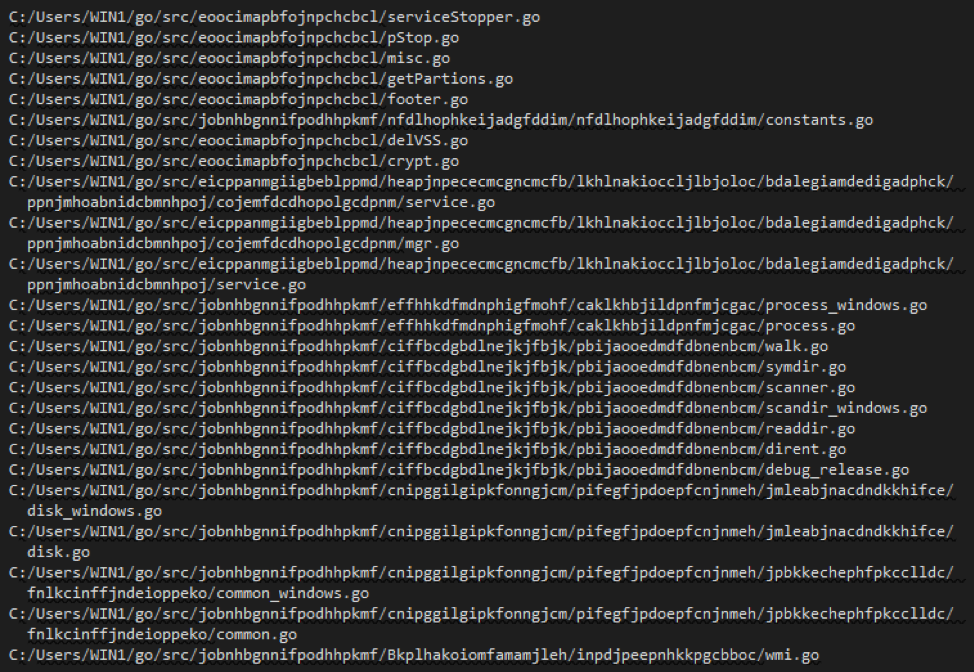

Analysis of the binary indicates multiple, custom Go libraries are used to construct and ensure execution, as shown in Figure 1.

On its own, the binary consists of multiple encoded strings. However, the encoding schema can be identified and reversed, and publicly available analysis was provided as early as 07 January 2020. [6] Reviewing the encoded strings along with monitoring malware execution in a sandbox environment identifies the ransomware’s program flow.

First, the malware checks for the existence of a Mutex value, “EKANS”, on the victim. If present, the ransomware will stop with a message “already encrypted!”. Otherwise, the Mutex value is set and encryption moves forward using standard encryption library functions. Primary functionality on victim systems is achieved via Windows Management Interface (WMI) calls, which begins executing encryption operations and removes Volume Shadow Copy backups on the victim.

Before proceeding to file encryption operations, the ransomware force stops (“kills”) processes listed by process name in a hard-coded list within the encoded strings of the malware. A full list with assessed process function or relationship is provided in Appendix A of this report. While some of the referenced processes appear to relate to security or management software (e.g., Qihoo 360 Safeguard and Microsoft System Center), the majority of the listed processes concern databases (e.g., Microsoft SQL Server), data backup solutions (e.g., IBM Tivoli), or ICS-related processes.

ICS products referenced include numerous references to GE’s Proficy data historian, with both client and server processes included. [7] Additional ICS-specific functionality referenced includes GE Fanuc licensing server services and Honeywell’s HMIWeb application. [8] Remaining ICS-related items consist of remote monitoring (e.g., historian-like) or licensing server instance such as FLEXNet and Sentinel HASP license managers and ThingWorx Industrial Connectivity Suite. [9] As indicated previously, the malware performs no action other than forcibly stopping the referenced process. As such, the malware has no capability to inject commands into or otherwise manipulate ICS-related processes. However, execution on the right system (e.g., a data historian) would induce a loss of view condition within the network.

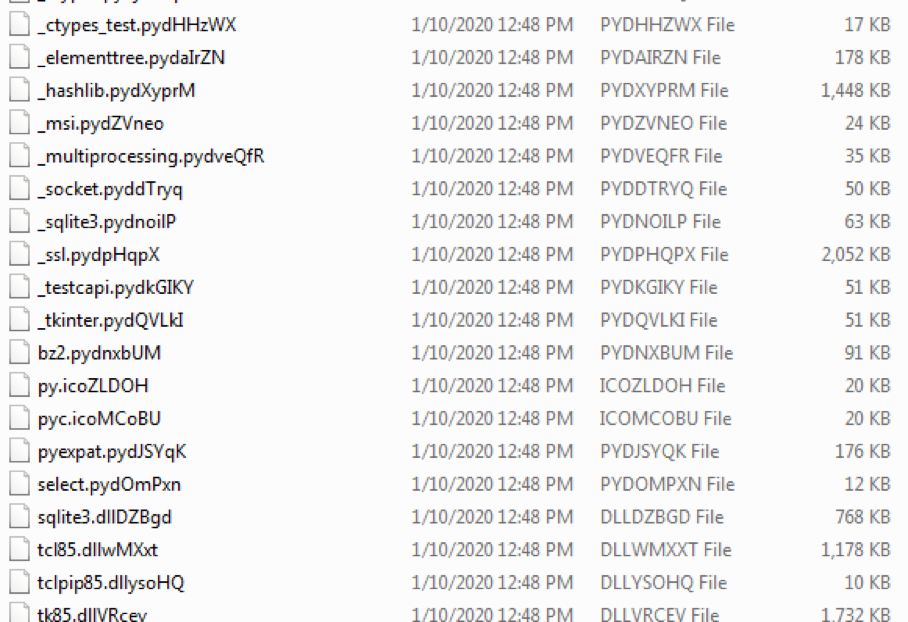

Files are renamed after encryption by appending a random five character (upper- and lower-case letters) to the original file extension. For example, as shown in Figure 2, Python PYD files are encrypted and additional characters added to the PYD extension.

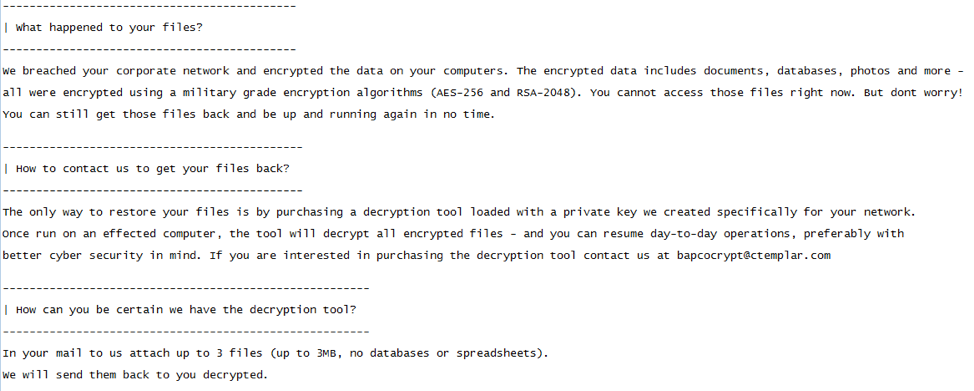

Following process stop and encryption actions, EKANS drops a ransom note to the root of the system drive (typically C:\) and the active user’s desktop. The ransom note is provided in Figure 3.

User access to the encrypted system is maintained throughout the process, and the system does not reboot, shutdown, or close remote access channels. This differentiates EKANS from more disruptive ransomware such as the LockerGoga variant deployed at Norsk Hydro in March 2019. [10] The email address in the ransomware uses a privacy-focused email service, similar to Protonmail, called CTemplar. [11]

Analyst Note: The response email, bapcocryp[AT]ctemplar[.]com, appears similar to Bapco, the Bahrain state oil company. [12] Recent reporting claims that Bapco was the victim of the late December 2019 ZeroCleare wiper variant Dustman. [13] While the email address is provocative in light of this news, the EKANS sample appears unrelated to the Dustman event. The EKANS sample was first identified in a commercial virus repository on 26 December 2019, while the Dustman event took place on 29/30 December 2019. One possibility is that EKANS was in fact used at Bapco in an incident prior to Dustman, while another is that current public reporting is confusing the Dustman incident (which all available information indicates is focused on Saudi Arabia) with a widespread and potentially disruptive ransomware event at Bapco occurring around the same time. In either case, any links between EKANS, the Bapco incident, and the Dustman wiper appear circumstantial given available evidence.

EKANS possesses no built-in propagation or spreading mechanism. The malware must instead be launched either interactively or via script to infect a host. As such, EKANS follows a trend observed in other ransomware families such as Ryuk and MEGACORTEX among others, where self-propagation is avoided in favor of performing large-scale compromise of an enterprise network. Once achieved, ransomware can be seeded and scheduled throughout the network via script, Active Directory compromise, or some other mechanism to achieve simultaneous infection and system disruption.

EKANS Relationship to MEGACORTEX

While researching EKANS and the processes identified in Appendix A, Dragos made a connection to another ransomware family, MEGACORTEX. [14] Process kill activity similar to EKANS was observed in a newer, “version 2” variant of MEGACORTEX in mid-2019, as publicly analyzed and reported by Accenture. [15] The specific MEGACORTEX sample that also references ICS processes has the following characteristics:

MD5: 53dddbb304c79ae293f98e0b151c6b28

SHA1: 2632529b0fb7ed46461c406f733c047a6cd4c591

SHA256: 873aa376573288fcf56711b5689f9d2cf457b76bbc93d4e40ef9d7a27b7be466

While the list of processes targeted in EKANS is relatively short and focused (64 total items), the newer version of MEGACORTEX contains over 1,000 referenced items. The vast majority of the processes listed relate to security solutions or similar tools. However, all of the items referenced in the EKANS ICS list are also present in the MEGACORTEX list, and no additional items are present in the MEGACORTEX list with ICS significance. Based on this information, it appears EKANS is not unique, or at least not first, in targeting ICS-related processes.

Instead EKANS represents an obfuscated, hardened ransomware variant based on prior MEGACORTEX activity.

ICS Significance and Implications

Past concerns with ransomware in ICS environments focused on propagation mechanisms. Essentially, IT-focused ransomware could impact control system environments if they could migrate into Windows-based portions of control system networks, thus disrupting operations. As such, any ICS disruption caused by ransomware represented the results of overly-aggressive malware propagation leading to ICS impacts.

EKANS (and apparently some versions of MEGACORTEX) shift this narrative as ICS-specific functionality is directly referenced within the malware. While some of these processes may reside in typical enterprise IT networks, such as Proficy servers or Microsoft SQL servers, inclusion of HMI software, historian clients, and additional items indicates some minimal, albeit crude, awareness of control system environment processes and functionality.

The actual level of impact EKANS or ICS-aware MEGACORTEX may have on industrial environments is unclear. Targeting historian and data gathering processes at both the client and server level imposes significant costs on an organization and could induce a loss of view condition within the overall plant environment. The impacts for licensing server and HMI process termination are less clear, as other processes may still be in play to enable functionality and fallbacks or “grace periods” for licensing servers may enable continued operations for some time absent the license management system.

“EKANS and its presumed parent MEGACORTEX variant represent a unique and specific risk to industrial operations not previously observed in ransomware malware operations.”

Nonetheless, this uncertainty remains unacceptable given the possibility to produce inadvertent loss of control situations depending on precise environment configuration and process links. As a result, EKANS and its presumed parent MEGACORTEX variant represent a unique and specific risk to industrial operations not previously observed in ransomware operations. While some organizations have the emergency recourse of falling back into “manual mode” operations, the costs and inefficiencies of doing so (if such a change-over happens absent friction) are still substantial. Given these aspects, EKANS and its parent present specific and unique risks and cost-imposition scenarios for industrial environments.

Evaluating Alleged Links to Iran

One particular item of interest in both the vendor blog post [16] and Bloomberg article [17] on EKANS activity is an emphasis on supposedly proven links to “Iranian strategic interests.” While any connection to “strategic interests” are possible given the size and scope of most states’ long-term strategy, Dragos analysis finds any such link to be incredibly tenuous based upon available evidence. Arguments offered in favor of Iranian involvement include overlap with previously reported Dustman wiper activity, presumed unlikelihood of having overlapping intrusions in the same environment at the same time, and alleged technical similarities between EKANS and known Iran-linked operations.

In all three cases, current evidence does not support asserting an association with Iranian cyber operations. [18]

First, the correlation with Dustman is odd as all available evidence indicates Dustman took place at the end of December 2019 while EKANS appears to have been active in mid-December 2019. Furthermore, Dustman authoritative reporting emerged from Saudi Arabia and not Bahrain, implying Dustman activity largely focused on this country. [19] While possible that Bapco may have been impacted by both events, even if this is the case such an observation does not necessitate or even imply a link between events.

Which leads to the second concern, where vendor reporting and media quotes indicate it is unlikely two separate entities would be engaged in a victim environment simultaneously. Yet as seen in high-profile cases such as the 2016 Democratic National Committee intrusion, [20] such operations do exist, and a plethora of other cases indicate they may not be rare. Thus, if Bapco did experience a Dustman event and Bapco is the victim of EKANS as well, these two events represent a coincidence and prove no relationship or link to an overall coordinating authority on their own.

References are made in the two referenced sources on technical “markers” demonstrating EKANS similarity to Iran-linked events. Unfortunately, no such markers are present. Past, publicly-reported Iranian-associated IT disruptive activity exclusively focused on using Disttrack-like malware variants weaponizing the ElodS RawDisk driver to render victim machines unusable, from the original Shamoon through ZeroCleare and Dustman. [21] Absent any additional context, EKANS instead appears to be a fairly standard ransomware variant, albeit with some additional concerning functionality. While there are examples of ransomware-like malware being used as a means to achieve widespread destruction, [22] no evidence exists that EKANS was designed to mimic such functionality. Furthermore, past experience both in cyber and physical realms (since Iranian-linked interests were happy to launch missiles and destructive drones against Saudi oil infrastructure in September 2019) [23] adds a significant burden to the argument such an actor would desire or need to obfuscate operations.

Overall, no strong or compelling evidence exists to link EKANS with Iranian strategic interests. While a link to Bapco is possible given the ransom email address, any further correlation to Iranian-associated activity is simply not supported by any available evidence.

Mitigations

At present, Dragos is not aware of how EKANS distributes itself within victim networks. Primary defense against ransomware such as EKANS relies on preventing it from reaching or spreading through the network in the first place.

Host

- Unlike some other recent ransomware variants, EKANS is not code signed. Implementing controls in control system networks to prohibit the execution of unsigned binaries can therefore mitigate against the execution of malware such as this. Unfortunately, many legitimate vendor software packages continue to be distributed in unsigned form, so this mitigation strategy may not be practical in many instances.

- Similar to the above but relying on more generic mechanisms, organizations can prohibit or at least monitor for the execution of previously unseen executables from non-standard or non-update sources. Again, while imperfect given how some legitimate software packages are created and distributed, this may nonetheless serve at least as an initial alarm to prompt further investigation and possibly limit the spread of malicious software in sensitive networks.

- Within the context of ICS historian operations specifically, organizations can potentially identify a disruptive attack in progress by implementing logic or monitoring on their historian (such as GE Proficy in this case) to identify cases where multiple endpoints cease communication and reporting to the historian at approximately the same time. While systems may still be offline or compromised, identifying this datapoint early in the investigation will facilitate root cause analysis into the event by identifying potential ICS-specific functionality, such as that displayed in EKANS.

- Although a frequent recommendation for ransomware events, organizations must place emphasis on generating regular backups of important files and systems and storing them in a secure location not easily accessible from the regular network. For ICS operations in particular, backups must include last known-good configuration data, project files, and related items to enable rapid recovery should a disruptive event occur.

Network

- Where possible, identify the transfer of unknown binary files via network means from enterprise networks to control system enclaves. While imperfect, identifying when executable code enters the ICS environment can at least allow defenders to correlate this activity with other suspicious observations (such as new logon or promiscuous logon activity) that may indicate an intrusion is underway.

- Dragos’ Professional Services team has worked with companies disrupted by ransomware attacks. The following are some key lessons learned from responding to ransomware incidents at industrial companies.

Beware your backups

- Many ransomware attacks also impact backup infrastructure. In a recent ransomware incident Dragos responded to, attackers encrypted the Synology network attached storage (NAS) that was mounted as a Sever Message Block (SMB) share to all systems to store backups. Luckily, an engineer had previously decided to take a copy of the backups on an external drive. Unfortunately, the backups were about 18 months old, so the victim lost a lot of production data, and the engineering enhancements and logic changes made during that time. In addition to maintaining offline backups, backup procedures should consider not only systems, but critical data. While backing up a system may be fine every three months for example, critical data required for business operations may need to be available down to the day or hour. Companies should ensure this information is identified and categorized based on criticality and available if all systems are encrypted. Additionally, Dragos recommended that logic is backed up after any significant changes.

Don’t neglect the control layer

- When performing recovery efforts on a plant network, primary focus may be on restoring supervisory control, like impacted Windows assets. However, it may be possible for attackers to use ransomware to cover secondary process impacts or cover up an attacker’s true intent. In recent Dragos investigations, we have found evidence of attackers probing automation controllers, likely network enumeration and scanning, however this is difficult to verify. In this case, the only controller logic available dated back just 18 months, so performing logic verification identified a lot of unexpected changes and it was unclear whether attackers or operators who forgot to document changes were responsible. Dragos recommends operators ensure controller logic is backed up frequently and procedures are available to verify logic after an incident. Additionally, asset owners and operators may want to investigate with vendors to identify the type of security logs available on the controllers.

Time is of the essence

- Adversaries responsible for ransomware incidents act quickly. In many cases, adversaries are not interested in the underlying infrastructure or data, they just want to encrypt the systems as quickly as possible. In the customer ransomware incident mentioned above, responders observed a turnaround of less than 24 hours between initial access, obtaining domain admin, and plant-wide ransomware deployment. Attackers in this event dropped more than 30 tools on the end points and brute forced authentication credentials. Proper monitoring and response procedures could detect them and block the attack; however, responders need to act quickly.

Conclusions

EKANS ransomware is unique as it joins a handful of ICS-specific malware variants, such as Havex and CRASHOVERRIDE, in having specific references to industrial processes. At the same time, EKANS actual implementation of such functionality is extremely primitive with an indeterminate industrial impact.

EKANS malware and its attempt to cease particular industrial-related processes is further evolution and context around the growing cyber threat to industrial control systems, but EKANS itself is more a novelty than a discrete and worrying risk.

Nonetheless, EKANS (and its likely predecessor MEGACORTEX) represent an adversary evolution to hold control system environments specifically at risk. As such, EKANS despite its limited functionality and nature represents a relatively new and deeply concerning evolution in ICS-targeting malware. Whereas previously ICS-specific or ICS-related malware was solely the playground of state-sponsored entities, EKANS appears to indicate non-state elements pursuing financial gain are now involved in this space as well, even if only at a very primitive level. As a result, it is incumbent upon ICS asset owners and operators to learn from not only how EKANS itself functions, but the myriad ways in which malicious software like EKANS can propagate and be distributed in control system environments to prepare actionable, relevant defense.

Appendix A – EKANS Targeted Processes

| Process | Description |

| bluestripecollector.exe | BlueStripe Data Collector |

| ccflic0.exe | Proficy Licensing |

| ccflic4.exe | Proficy Licensing |

| cdm.exe | Nimsoft Related |

| certificateprovider.exe | Ambiguous |

| client.exe | Ambiguous |

| client64.exe | Ambiguous |

| collwrap.exe | BlueStripe Data Collector |

| config_api_service.exe | ThingWorx Industrial Connectivity Suite, Ambiguous |

| dsmcsvc.exe | Tivoli Storage Manager Client |

| epmd.exe | RabbitMQ Server (SolarWinds) |

| erlsrv.exe | Erlang |

| fnplicensingservice.exe | FLEXNet Licensing Service |

| hasplmv.exe | Sentinel Hasp License Manager |

| hdb.exe | Honeywell HMIWeb |

| healthservice.exe | Microsoft SCCM |

| ilicensevc.exe | GE Fanuc Licenseing |

| inet_gethost.exe | Erlang |

| keysvc.exe | Ambiguous |

| managementagenthost.exe | VMWare CAF Management Agent Service |

| monitoringhost.exe | Microsoft SCCM |

| msdtssrvr.exe | Microsoft SQL Server Integration Service |

| msmdsrv.exe | Microsoft SQL Server Analysis Services |

| mustnotificationux.exe | Microsoft Update Notification Service |

| n.exe | Ambiguous |

| nimbus.exe | Broadcom Nimbus |

| npmdagent.exe | Microsoft OMS Agent |

| ntevl.exe | Nimsoft Monitor |

| ntservices.exe | 360 Total Security |

| pralarmmgr.exe | Proficy Related |

| prcalculationmgr.exe | Proficy Historian Data Calculation Service |

| prconfigmgr.exe | Proficy Related |

| prdatabasemgr.exe | Proficy Related |

| premailengine.exe | Proficy Related |

| preventmgr.exe | Proficy Related |

| prftpengine.exe | Proficy Related |

| prgateway.exe | Proficy Secure Gateway |

| prlicensingmgr.exe | Proficy License Server Manager |

| proficyadministrator.exe | Proficy Related |

| proficyclient.exe | Proficy Related |

| proficypublisherservice.exe | Proficy Related |

| proficyserver.exe | Proficy Server |

| proficysts.exe | Proficy Related |

| prprintserver.exe | Proficy Related |

| prproficymgr.exe | Proficy Plant Applications |

| prrds.exe | Proficy Remote Data Service |

| prreader.exe | Proficy Historian Data Calculation Service |

| prrouter.exe | Proficy Related |

| prschedulemgr.exe | Proficy Related |

| prstubber.exe | Proficy Related |

| prsummarymgr.exe | Proficy Related |

| prwriter.exe | Proficy Historian Data Calculation Service |

| reportingservicesservice.exe | Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Service |

| server_eventlog.exe | Proficy Event Log Service, Ambiguous |

| server_runtime.exe | Proficy Related, Ambiguous |

| spooler.exe | Ambiguous |

| sqlservr.exe | Microsoft SQL Server |

| taskhostw.exe | Windows OS |

| vgauthservice.exe | VMWare Guest Authentication Service |

| vmacthlp.exe | VMWare Activation Helper |

| vmtoolsd.exe | VMWare Tools Service |

| win32sysinfo.exe | RabbitMQ |

| winvnc4.exe | WinVNC Client |

| workflowresttest.exe | Ambiguous |

Footnotes

[1] Vitali Kremez; SNAKE Ransomware is the Next Threat Targeting Business Networks – BleepingComputer; Dragos WorldView customers should consult TR-2020-02 EKANS Ransomware and ICS Operations

[2] Ransomware Linked to Iran, Targets Industrial Controls – Bloomberg; Snake: Industrial-Focused Ransomware with Ties to Iran – Otorio

[3] The Epic Turla (snake/Uroburos) Attacks – Kaspersky; Turla – MITRE

[4] Implications of IT Ransomware for ICS Environments – Dragos

[5] Out of Control: Ransomware for Industrial Control Systems – David Formby, Srikar Durbha, and Raheem Beyah; ClearEnergy – The “In the Wild” SCADA Ransomware Attacks that Never Existed – BleepingComputer

[6] Open Mal Analysis Notes – Sysopfb (GitHub)

[7] Proficy Historian – GE

[8] HMIWeb Solutions – Honeywell; Fanuc

[9] ThingWorx Industrial Connectivity Product Brief – PTC; FlexNet Licensing – Flexera; Sentinel HASP – Gemalto

[10] Ransomware or Wiper? LockerGoga Straddles the Line – Cisco Talos; Dragos WorldView subscribers should also review TR-2019-30 Revisiting LockerGoga

[11] CTemplar

[12] Our Company – Bapco

[13] New Iranian Data Wiper Malware Hits Bapco, Bahrain’s National Oil Company – ZDNet; Dragos WorldView subscribers should also review AA-2020-01.2 Possible Wiper Activity in the Middle East and TR-2020-03 Dustman Wiper Activity in the Gulf Region

[14] MegaCortex Ransomware Spotted Attacking Enterprise Networks – TrendMicro

[15] Technical Analysis of MegaCortex Version 2 Ransomware – Accenture

[16] Snake: Industrial-focused Ransomware with Ties to Iran – Otorio

[17] Ransomware Linked to Iran, Targets Industrial Controls – Bloomberg

[18] Getting the Story Right, and Why It Matters – Joe Slowik

[20] CrowdStrike’s Word with the Democratic National Committee: Setting the Record Straight – Crowdstrike

[21] Shamoon2: Return of the Disttrack Wiper – Palo Alto Unit42; RawDisk – MITRE; New Destructive Wiper “ZeroCleare” Targets Energy Sector in the Middle East – IBM; Shamoon: Destructive Threat Re-Emerges with New Sting in Its Tail – Symantec

[22] The Untold Story of NotPetya, the Most Devastating Cyberattack in History – Wired

[23] Saudi Oil Attack Photos Implicate Iran, U.S. Says; Trump Hints at Military Action – The New York Times

Ready to put your insights into action?

Take the next steps and contact our team today.